- The Original of Laura: (Dying is Fun) a Novel in Fragments

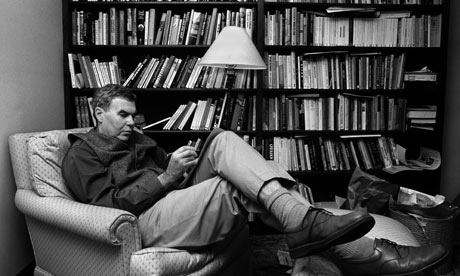

- by Vladimir Nabokov

- 304pp,

- Penguin Classics,

- £25

". . . I regarded Paris, with its gray-toned days and charcoal nights, merely as the chance setting for the most authentic and faithful joys of my life: the coloured phrase in my mind under the drizzle, the white page under the desk lamp awaiting me in my humble home."

Well, the creative joy is authentic; and yet it isn't faithful (in common with pretty well the entire cast of Nabokov's fictional women, creative joy, in the end, is sadistically fickle). Writing remains a very interesting job, but destiny, or "fat Fate", as Humbert Humbert calls it, has arranged a very interesting retribution. Writers lead a double life. And they die doubly, too. This is modern literature's dirty little secret. Writers die twice: once when the body dies, and once when the talent dies.

Nabokov composed The Original of Laura, or what we have of it, against the clock of doom (a series of sickening falls, then hospital infections, then bronchial collapse). It is not "A novel in fragments", as the cover states; it is immediately recognisable as a longish short story struggling to become a novella. In this palatial edition, every left-hand page is blank, and every right-hand page reproduces Nabokov's manuscript (with its robust handwriting and fragile spelling – "bycycle", "stomack", "suprize"), plus the text in typed print (and infested with square brackets). It is nice, I dare say, to see those world-famous index cards up close; but in truth there is little in Laura that reverberates in the mind. "Auroral rumbles and bangs had begun jolting the cold misty city": in this we hear an echo of the Nabokovian music. And in the following we glimpse the funny and fearless Nabokovian disdain for our "abject physicality":

Nabokov composed The Original of Laura, or what we have of it, against the clock of doom (a series of sickening falls, then hospital infections, then bronchial collapse). It is not "A novel in fragments", as the cover states; it is immediately recognisable as a longish short story struggling to become a novella. In this palatial edition, every left-hand page is blank, and every right-hand page reproduces Nabokov's manuscript (with its robust handwriting and fragile spelling – "bycycle", "stomack", "suprize"), plus the text in typed print (and infested with square brackets). It is nice, I dare say, to see those world-famous index cards up close; but in truth there is little in Laura that reverberates in the mind. "Auroral rumbles and bangs had begun jolting the cold misty city": in this we hear an echo of the Nabokovian music. And in the following we glimpse the funny and fearless Nabokovian disdain for our "abject physicality":

"I loathe my belly, that trunkful of bowels, which I have to carry around, and everything connected with it – the wrong food, heartburn, constipation's leaden load, or else indigestion with a first installment of hot filth pouring out of me in a public toilet . . ."

Otherwise and in general Laura is somewhere between larva and pupa (to use a lepidopteral metaphor), and very far from the finished imago.

Apart from a welcome flurry of interest in the work, the only thing this relic will effect, I fear, is the slight exacerbation of what is already a problem from hell. It is infernal, for me, because I bow to no one in my love for this great and greatly inspiring genius. And yet Nabokov, in his decline, imposes on even the keenest reader a horrible brew of piety, literal-mindedness, vulgarity and philistinism. Nothing much, in Laura, qualifies as a theme (ie, as a structural or at least a recurring motif). But we do notice the appearance of a certain Hubert H Hubert (a reeking Englishman who slobbers over a pre-teen's bed), we do notice the 24-year-old vamp with 12-year-old breasts ("pale squinty nipples and firm form"), and we do notice the fevered dream about a juvenile love ("her little bottom, so smooth, so moonlit"). In other words, Laura joins The Enchanter (1939), Lolita (1955), Ada (1970), Transparent Things (1972), and Look at the Harlequins! (1974) in unignorably concerning itself with the sexual despoiliation of very young girls.

Six fictions: six fictions, two or perhaps three of which are spectacular masterpieces. You will, I hope, admit that the hellish problem is at least Nabokovian in its complexity and ticklishness. For no human being in the history of the world has done more to vivify the cruelty, the violence, and the dismal squalor of this particular crime. The problem, which turns out to be an aesthetic problem, and not quite a moral one, has to do with the intimate malice of age.

❦

The word we want is not the legalistic "paedophilia", which in any case deceitfully translates as "fondness for children". The word we want is "nympholepsy", which doesn't quite mean what you think it means. It means "frenzy caused by desire for the unattainable", and is rightly characterised by my COD as literary. As such, nympholepsy is a legitimate, indeed an almost inevitable subject for this very singular talent. "Nabokov's is really an amorous style," John Updike lucidly observed: "It yearns to clasp diaphonous exactitude into its hairy arms." With the later Nabokov, though, nympholepsy crumbles into its etymology – "from Gk numpholeptos 'caught by nymphs', on the pattern of EPILEPSY"; "from Gk epilepsia, from epilambanein 'seize, attack'".

Dreamed up in 1930s Berlin (with Hitler's voice spluttering out from the rooftop loudspeakers), and written in Paris (post-Kristallnacht, at the start of the Nabokovs' frenetic flight from Europe), The Enchanter is a vicious triumph, brilliantly and almost osmotically translated from the Russian by Dmitri Nabokov in 1987, 10 years after his father's death.As a narrative it is logistically identical to the first half of Lolita: the rapist will marry – and perhaps murder – the mother, and then negotiate the child. Unlike the redoubtable Charlotte Haze ("she of the noble nipple and massive thigh"), the nameless widow in The Enchanter is already promisingly frail, her large body warped out of symmetry by hospitalisations and surgeons' knives. And this is why her suitor reluctantly rejects the idea of poison: "Besides, they'll inevitably open her up, out of sheer habit."

The wedding takes place, and so does the wedding night: ". . . and it was perfectly clear that he (little Gulliver)" would be physically unable to tackle "those multiple caverns" and "the repulsively listing conformation of her ponderous pelvis". But "in the middle of his farewell speeches about his migraine", things take an unexpected turn,

"so that, after the fact, it was with astonishment that he discovered the corpse of the miraculously vanquished giantess and gazed at the moiré girdle that almost totally concealed her scar."

Soon the mother is dead for real, and the enchanter is alone with his 12-year-old. "The lone wolf was getting ready to don Granny's nightcap."

In Lolita, Humbert has "strenuous sexual intercourse" with his nymphet at least twice a day for two years. In The Enchanter there is a single delectation – non-invasive, voyeuristic, masturbatory. In the hotel room the girl is asleep, and naked; "he began passing his magic wand above her body", measuring her "with an enchanted yardstick". She awakes, she looks at "his rearing nudity", and she screams. With his obsession now reduced to a cooling smear on the raincoat he throws on, our enchanter runs out into the street, seeking to rid himself, by any means, of a world "already-looked-at" and "no-longer-needed". A tramcar grinds into sight, and under

"this growing, grinning, megathundering mass, this instantaneous cinema of dismemberment – that's it, drag me under, tear at my frailty – I'm travelling flattened, on my smacked-down face . . . don't rip me to pieces – you're shredding me, I've had enough . . . Zigzag gymnastics of lightning, spectogram of a thunderbolt's split seconds – and the film of life had burst."

❦

In moral terms The Enchanter is sulphurously direct. Lolita, by contrast, is delicately cumulative; but in its judgment of Humbert's abomination it is, if anything, the more severe. To establish this it is necessary to adduce only two key points. First, the fate of its tragic heroine. No unprepared reader could be expected to notice that Lolita meets a terrible end on page two of the novel that bears her name: "Mrs 'Richard F Schiller' died in childbed", says the "editor" in his Foreword, "giving birth to a still-born girl . . . in Gray Star, a settlement in the remotest Northwest"; and the novel is almost over by the time Mrs Richard F Schiller (ie, Lo) briefly appears. Thus we note, with a parenthetical gasp, the size of Nabokov's gamble on greatness. "Curiously enough, one cannot read a book," he once announced (at the lectern), "one can only reread it." Nabokov knew that Lolita would be reread, and re-reread. He knew that we would eventually absorb Lolita's fate – her stolen childhood, her stolen womanhood. Gray Star, he wrote, is "the capital town of the book". The shifting half-tone – gray star, pale fire, torpid smoke: this is the Nabokovian crux.

The second fundamental point is the description of a recurring dream that shadows Humbert after Lolita has flown (she absconds with the cynically carnal Quilty). It is also proof of the fact that style, that prose itself, can control morality. Who would want to do something that gave them dreams like these?

". . . she did haunt my sleep but she appeared there in strange and ludicrous disguises as Valeria or Charlotte [his ex-wives], or a cross between them. That complex ghost would come to me, shedding shift after shift, in an atmosphere of great melancholy and disgust, and would recline in dull invitation on some narrow board or hard settee, with flesh ajar like therubber valve of a soccer ball's bladder. I would find myself, dentures fractured or hopelessly misplaced, in horrible chambres garnies, where I would be entertained at tedious vivisecting parties that generally ended with Charlotte or Valeria weeping in my bleeding arms and being tenderly kissed by my brotherly lips in a dream disorder of auctioneered Viennese bric-a-brac, pity, impotence and the brown wigs of tragic old women who had just been gassed."

That final phrase, with its clear allusion, reminds us of the painful and tender diffidence with which Nabokov wrote about the century's terminal crime. His father, the distinguished liberal statesman (whom Trotsky loathed), was shot dead by a fascist thug in Berlin; and Nabokov's homosexual brother, Sergey, was murdered in a Nazi concentration camp ("What a joy you are well, alive, in good spirits," Nabokov wrote to his sister Elena, from the US to the USSR, in November 1945. "Poor, poor Seryozha . . . !"). Nabokov's wife, Véra, was Jewish, and so, therefore, was their son (born in 1934); and there is a strong likelihood that if the Nabokovs had failed to escape from France when they did (in May 1940, with the Wehrmacht 70 miles from Paris), they would have joined the scores of thousands of undesirables delivered by Vichy to the Reich.

In his fiction, to my knowledge, Nabokov wrote about the Holocaust at paragraph length only once – in the incomparable Pnin (1957). Other references, as in Lolita, are glancing. Take, for example, this one-sentence demonstration of genius from the insanely inspired six-page short story "Signs and Symbols" (it is a description of a Jewish matriarch):

"Aunt Rosa, a fussy, angular, wild-eyed old lady, who had lived in a tremulous world of bad news, bankruptcies, train accidents, cancerous growths – until the Germans put her to death, together with all the people she had worried about."

Pnin goes further. At an émigré houseparty in rural America a Madam Shpolyanski mentions her cousin, Mira, and asks Timofey Pnin if he has heard of her "terrible end". "Indeed, I have," Pnin answers. Gentle Timofey sits on alone in the twilight. Then Nabokov gives us this:

"What chatty Madam Shpolyanski mentioned had conjured up Mira's image with unusual force. This was disturbing. Only in the detachment of an incurable complaint, in the sanity of near death, could one cope with this for a moment. In order to exist rationally, Pnin had taught himself . . . never to remember Mira Belochkin – not because . . . the evocation of a youthful love affair, banal and brief, threatened his peace of mind . . . but because, if one were quite sincere with oneself, no conscience, and hence no consciousness, could be expected to subsist in a world where such things as Mira's death were possible. One had to forget – because one could not live with the thought that this graceful, fragile, tender young woman with those eyes, that smile, those gardens and snows in the background, had been brought in a cattle car and killed by an injection of phenol into the heart, into the gentle heart one had heard beating under one's lips in the dusk of the past."

How resonantly this passage chimes with Primo Levi's crucial observation that we cannot, we must not, "understand what happened". Because to "understand" it would be to "contain" it. "What happened" was "non-human", or "counter-human", and remains incomprehensible to human beings.

By linking Humbert Humbert's crime to the Shoah, and to "those whom the wind of death has scattered" (Paul Celan), Nabokov pushes out to the very limits of the moral universe. Like The Enchanter, Lolita is airtight, intact and entire. The frenzy of the unattainable desire is confronted, and framed, with stupendous courage and cunning. And so matters might have rested. But then came the meltdown of artistic self-possession – tumultuously announced, in 1970, by the arrival of Ada. When a writer starts to come off the rails, you expect skidmarks and broken glass; with Nabokov, naturally, the eruption is on the scale of a nuclear accident.

❦

I have read at least half a dozen Nabokov novels at least half a dozen times. And at least half a dozen times I have tried, and promptly failed, to read Ada ("Or Ardor: A Family Chronicle"). My first attempt took place about three decades ago. I put it down after the first chapter, with a curious sensation, a kind of negative tingle. Every five years or so (this became the pattern), I picked it up again; and after a while I began to articulate the difficulty: "But this is dead," I said to myself. The curious sensation, the negative tingle, is of course miserably familiar to me now: it is the reader's response to what seems to happen to all writers as they overstep the biblical span. The radiance, the life-giving power, begins to fade. Last summer I went away with Ada and locked myself up with it. And I was right. At 600 pages, two or three times Nabokov's usual fighting-weight, the novel is what homicide detectives call "a burster". It is a waterlogged corpse at the stage of maximal bloat.

When Finnegans Wake appeared, in 1939, it was greeted with wary respect – or with "terror-stricken praise", in the words of Jorge Luis Borges. Ada garnered plenty of terror-stricken praise; and the similarities between the two magna opera are in fact profound. Nabokov nominated Ulysses as his novel of the century, but he described Finnegans Wake as, variously, "formless and dull", "a cold pudding of a book", "a tragic failure" and "a frightful bore". Both novels seek to make a virtue of unbounded self-indulgence; they turn away, so to speak, and fold in on themselves. Literary talent has several ways of dying. With Joyce and Nabokov, we see a decisive loss of love for the reader – a loss of comity, of courtesy. The pleasures of writing, Nabokov said, "correspond exactly to the pleasures of reading"; and the two activities are in some sense indivisible. In Ada, that bond loosens and frays.

There is a weakness in Nabokov for "partricianism", as Saul Bellow called it (Nabokov the classic émigré, Bellow the classic immigrant). In the former's purely "Russian" novels (I mean the novels written in Russian that Nabokov did not himself translate), the male characters, in particular, have a self-magnifying quality: they are larger and louder than life. They don't walk – they "march" or "stride"; they don't eat and drink – they "munch" and "gulp"; they don't laugh – they "roar". They are very far from being the furtive, hesitant neurasthenics of mainstream anglophone fiction: they are brawny (and gifted) heart-throbs, who win all the fights and win all the girls. Pride, for them, is not a deadly sin but a cardinal virtue. Of course, we cannot do without this vein in Nabokov: it gives us, elsewhere, his magnificently comic hauteur. In Lolita, the superbity is meant to be funny; elsewhere, it is a trait that irony does not protect.

There is a weakness in Nabokov for "partricianism", as Saul Bellow called it (Nabokov the classic émigré, Bellow the classic immigrant). In the former's purely "Russian" novels (I mean the novels written in Russian that Nabokov did not himself translate), the male characters, in particular, have a self-magnifying quality: they are larger and louder than life. They don't walk – they "march" or "stride"; they don't eat and drink – they "munch" and "gulp"; they don't laugh – they "roar". They are very far from being the furtive, hesitant neurasthenics of mainstream anglophone fiction: they are brawny (and gifted) heart-throbs, who win all the fights and win all the girls. Pride, for them, is not a deadly sin but a cardinal virtue. Of course, we cannot do without this vein in Nabokov: it gives us, elsewhere, his magnificently comic hauteur. In Lolita, the superbity is meant to be funny; elsewhere, it is a trait that irony does not protect.

In Ada nabobism disastrously combines with a nympholepsy that is lavishly, monotonously, and frictionlessly gratified. Ada herself, at the outset, is 12; and Van Veen, her cousin (and half-sibling) is 14. As Ada starts to age, in adolescence, her tiny sister Lucette is also on hand to enliven their "strenuous trysts". On top of this, there is a running quasi-fantasy about an international chain of elite bordellos where girls as young as 11 can be "fondled and fouled". And Van's 60-year-old father (incidentally but typically) has a mistress who is barely out of single figures: she is 10. This interminable book is written in dense, erudite, alliterative, punsome, pore-clogging prose; and every character, without exception, sounds like late Henry James.

In common with Finnegans Wake, Ada probably does "work out" and "measure up" – the multilingual decoder, given enough time and nothing better to do, might eventually disentangle its toiling systems and symmetries, its lonely and comfortless labyrinths, and its glutinous nostalgies. What both novels signally lack, however, is any hint of narrative traction: they slip and they slide; they just can't hold the road. And then, too, with Ada, there is something altogether alien – a sense of monstrous entitlement, of unbridled, head-in-air seigneurism. Morally, this is the world for which the twisted Humbert thirsts: a world where "nothing matters", and "everything is allowed".

❦

This leaves us with Transparent Things (to which we will uneasily return) and Look at the Harlequins! – as well as the more or less negligible volume under review. "LATH!", as the author called it, just as he called The Original of Laura "TOOL", is the Nabokov swansong. It has some wonderful rumbles, and glimmers of unearthly colour, but it is hard-of-hearing and rheumy-eyed; and the little-girl theme is by now hardly more than a logo – part of the Nabokovian furniture, like mirrors, doubles, chess, butterflies. There is a visit to a motel called Lolita Lodge; there is a brief impersonation of Dumbert Dumbert. More centrally, the narrator, Vadim Vadimovich, suddenly finds himself in sole charge of his seldom-seen daughter, Bel, who, inexorably, is 12 years old.

Now, where does this thread lead?

". . . I was still deliriously happy, still seeing nothing wrong or dangerous, or absurd or downright cretinous, in the relationship between my daughter and me. Save for a few insignificant lapses – a few hot drops of overflowing tenderness, a gasp masked by a cough and that sort of stuff – my relations with her remained essentially innocent."

Well, the dismaying answer is that this thread leads nowhere. The only repurcussion, thematic or otherwise, is that Vadim ends up marrying one of Bel's classmates, who is 43 years his junior. And that is all.

Between the hysterical Ada and the doddery Look at the Harlequins! comes the mysterious, sinister and beautifully melancholic novella, Transparent Things: Nabokov's remission. Our hero, Hugh Person, a middle-grade American publisher, is an endearing misfit and sexual loser, like Timofey Pnin (Pnin regularly dines at a shabby little restaurant called The Egg and We, which he frequents out of "sheer sympathy with failure"). Four visits to Switzerland provide the cornerstones of this expert little piece, as Hugh shyly courts the exasperating flirt, Armande, and also monitors an aged, portly, decadent, and forbiddingly highbrow novelist called "Mr R".

Mr R is said to have debauched his stepdaughter (a friend of Armande's) when she was a child or at any rate a minor. The nympholeptic theme thus hovers over the story, and is reinforced, in one extraordinary scene, by the disclosure of Hugh's latent yearnings. A pitiful bumbler, with a treacherous libido (wiltings and premature ejaculations mark his "mediocre potency"), Hugh calls on Armande's villa, and her mother diverts him, while he waits, with some family snapshots. He comes across a photo of a naked Armande, aged 10:

"The visitor constucted a pile of albums to screen the flame of his interest . . . and returned several times to the pictures of little Armande in her bath, pressing a proboscidate rubber toy to her shiny stomach or standing up, dimple-bottomed, to be lathered. Another revelation of impuberal softness (its middle line just distinguishable from the less vertical grass-blade next to it) was afforded by a photo of her in which she sat in the buff on the grass, combing her sun-shot hair and spreading wide, in false perspective, the lovely legs of a giantess.

"He heard a toilet flush upstairs and with a guilty wince slapped the thick book shut. His retractile heart moodily withdrew, its throbs quietened . . ."

At first this passage seems shockingly anomalous. But then we reflect that Hugh's unconscious thoughts, his dreams, his insomnias ("night is always a giant"), are saturated with inarticulate dreads:

"He could not believe that decent people had the sort of obscene and absurd nightmares which shattered his night and continued to tingle throughout the day. Neither the incidental accounts of bad dreams reported by friends nor the case histories in Freudian dream books, with their hilarious elucidations, presented anything like the complicated vileness of his almost nightly experience."

Hugh marries Armande and then, years later, strangles her in his sleep. So it may be that Nabokov identifies the paedophiliac prompting as an urge towards violence and self-obliteration. Hugh Person's subliminal churning extracts a terrible revenge, in pathos and isolation (prison, madhouse), and demands the ultimate purgation: he is burnt to death in one of the most ravishing conflagrations in all literature. The torched hotel:

"Now flames were mounting the stairs, in pairs, in trios, in redskin file, hand in hand, tongue after tongue, conversing and humming happily. It was not, though, the heat of their flicker, but the acrid dark smoke that caused Person to retreat back into the room; excuse me, said a polite flamelet holding open the door he was vainly trying to close. The window banged with such force that its panes broke into a torrent of rubies . . . At last suffocation made him try to get out by climbing out and down, but there were no ledges or balconies on that side of the roaring house. As he reached the window a long lavender-tipped flame danced up to stop him with a graceful gesture of its gloved hand. Crumbling partitions of plaster and wood allowed human cries to reach him, and one of his last wrong ideas was that those were the shouts of people anxious to help him, and not the howls of fellow men."

❦

Left to themselves, The Enchanter, Lolita, and Transparent Things might have formed a lustrous and utterly unnerving trilogy. But they are not left to themselves; by sheer weight of numbers, by sheer iteration, the nympholepsy novels begin to infect one another – they cross-contaminate. We gratefully take all we can from them; and yet . . . Where else in the canon do we find such wayward fixity? In the awful itch of Lawrence, maybe, or in the murky sexual transpositions of Proust? No: you would need to venture to the very fringes of literature – Lewis Carroll, William Burroughs, the Marquis de Sade – to find an equivalent emphasis: an emphasis on activities we rightly and eternally hold to be unforgivable.

In fiction, of course, nobody ever gets hurt; the flaw, as I said, is not moral but aesthetic. And I intend no innnuendo by pointing out that Nabokov's obsession with nymphets has a parallel: the ponderous intrusiveness of his obsession with Freud – "the vulgar, shabby, fundamentally medieval world" of "the Viennese quack", with "its bitter little embryos, spying, from their natural nooks, upon the love life of their parents". Nabokov cherished the anarchy of the inner life, and Freud is excoriated because he sought to systematise it. Is there something rivalrous in this hatred? Well, in the end it is Nabokov, and not Freud, who emerges as our supreme poet of dreams (with Kafka), and our supreme poet of madness.

One commonsensical caveat persists, for all our literary-critical impartiality: writers like to write about the things they like to think about. And, to put it at its sternest, Nabokov's mind, during his last period, insufficiently honoured the innocence – insufficiently honoured the honour – of 12-year-old girls. In the three novels mentioned above he prepotently defends the emphasis; in Ada (that incontinent splurge), in Look at the Harlequins!, and now in The Original of Laura, he does not defend it. This leaves a faint but visible scar on the leviathan of his corpus.

❦

"Now, soyons raisonnable," says Quilty, staring down the barrel of Humbert's revolver. "You will only wound me hideously and then rot in jail while I recuperate in a tropical setting." All right, let us be reasonable. In his book about Updike, Nicholson Baker refers to an order of literary achievement that he calls "Prousto-Nabokovian". Yes, Prousto-Nabokovian, or Joyceo-Borgesian, or, for the Americans, Jameso-Bellovian. And it is at the highest table that Vladimir Nabokov coolly takes his place.

Lolita, Pnin, Despair (1936; translated by the author in 1966), and four or five short stories are immortal. King, Queen, Knave (1928, 1968), Laughter in the Dark (1932, 1936), The Enchanter, The Eye (1930), Bend Sinister (1947), Pale Fire (1962), and Transparent Things are ferociously accomplished; and little Mary (1925), his first novel, is a little beauty. Lectures on Literature (1980), Lectures on Russian Literature (1981), and Lectures on Don Quixote (1983), together with Strong Opinions (1973), constitute the shining record of a pre-eminent artist-critic. And the Selected Letters (1989), the Nabokov-Wilson Letters (1979), and that marshlight of an autobiography, Speak, Memory (1967), give us a four-dimensional portrait of a delightful and honourable man. The vice Nabokov most frequently reviled was "cruelty". And his gentleness of nature is most clearly seen in the loving attentiveness with which, in his fiction, he writes about animals. A minute's thought gives me the cat in King, Queen, Knave (washing itself with one hindleg raised "like a shouldered club"), the charming dogs and monkeys in Lolita, the shadow-tailed squirrel and the unforgettable ant in Pnin, and the sick bat in Pale Fire – creeping past "like a cripple with a broken umbrella".

They call it a "shimmer" – a glint, a glitter, a glisten. The Nabokovian essence is a miraculously fertile instability, where without warning the words detach themselves from the everyday and streak off like flares in a night sky, illuminating hidden versts of longing and terror. From Lolita, as the fateful cohabitation begins (nous connûmes, a Flaubertian intonation, means "we came to know"):

"Nous connûmes the various types of motor court operators, the reformed criminal, the retired teacher, and the business flop, among the males; and the motherly, pseudo-ladylike and madamic variants among the females. And sometimes trains would cry in the monstrously hot and humid night with heartrending and ominous plangency, mingling power and hysteria in one desperate scream."

--

Martin Amis, The Guardian, Saturday 14 November 2009

cropped.jpg)

.jpg)

cropped.jpg)

2.jpg)

Cropped.jpg)

cropped.jpg)

4.jpg)